Prelude

It was the late-autumn of 2016. The northern winds had replaced the southern one. The neem tree beside my house began to shed its leaves. Walking the streets on a Sunday evening with my partner, with the cars whooshing past, I thrust my hands into my pockets, while she wrapped a scarf around her neck. There was a slight chill in the air. After a long, detailed discussion; negotiations, arguments and debates, we arrived at a conclusion that it would be Bhutan.

The planning began. March in Bhutan would be impossible with tourists flocking there in droves. Our best bet was the end of January, which was off-season for tourists, meaning hotels would be cheaper, and we could probably witness snowfall. The duration of our trip came down to a week, after chopping down cities due to budget constraints. We decided to go by land, and return by air; because it was cheaper, and why not, since the road trip from the border town, Phuntsholing to Thimphu was breathtakingly scenic according to blogs and articles.

The woman at the Royal Bhutan Consulate on Ballygunge Circular Road gave us the requisite forms for the permit that would allow us to cross over by land. We could have obtained it at the border, but since we were reaching there on a weekend, we couldn’t risk it. She asked us to submit the forms a month in advance and assured us of getting the permits in time. In the same building was the office of Druk Air, and we purchased the return tickets: Paro—Kolkata.

Bhutan would be cold in January, and we needed warm woollens, jackets and boots. So, the shopping began. We also started hoarding hundred rupee banknotes, as our hon’ble prime minister had demonetised the high-value banknotes and replaced them with even higher valued banknotes in his absurd bid to eradicate the long-standing problem of black-money plaguing our nation. Although they accept our currency in Bhutan—since both the countries follow a currency-pegged system—the woman at the consulate had warned us that the Bhutanese might be sceptical of the new banknotes.

But when we reached the consulate a month in advance, with our filled-up forms, the lady dropped a bomb-shell. She said that the consulate had stopped accepting any more requests for permits; they have reached a limit or something. She asked us to get them at the border. I tried to communicate to her that we had done just as she had asked and that we were reaching Phuntsholing on a Saturday, which meant that we’d have to wait until Monday to get the permits; in other words, cutting down a day and a half from our week-long trip. I did try and raise my volume a bit, but she just shrugged, with a look that conveyed—You better leave, I have important stuff to do.

I stormed out of the consulate cursing, kicking the pavement, wondering how we would spend an entire day in Phuntsholing. The best that I could come up with was watching crocodiles in a breeding centre, basking in the January sun, while we could have reached Thimphu if we had gotten the permits from Kolkata. The flight to Bagdogra was already booked, and worse, it was non-refundable. I was crossed the whole evening; we ate in silence and headed home. Later, when I calmed down, I realised that it would be wise to take a flight from Bagdogra to Paro. Yes, we would still lose half a day, but at least it would be better than watching crocodiles at a zoo. My partner went to the airline’s office and purchased the tickets the following day. The young woman at the office found it exceptionally weird when she heard our earlier plan.

DAY 0: KOLKATA TO BAGDOGRA

The flight to Bagdogra was uneventful. We reached there around noon and checked into a hotel nearby, an albeit shady one, where policemen did rounds, raiding hotel rooms in search of under-aged couples, especially girls who had been lured by pervert men. The owner should have informed us of the possibility of their visit so that we would have prepared ourselves for the afternoon knock and shock. The evening was spent walking the markets of Bagdogra.

DAY 1: BAGDOGRA – PARO – THIMPHU

The next morning, after breakfast, we headed to the airport. The driver who we had prearranged the previous day, convincingly duped us with the fare, but at least he was punctual—an admirable quality nonetheless.

The airport was crowded. It’s a small military airport, turned into an international airport that is unequipped to handle the traffic. We got our boarding passes and passed through emigration. The emigration officer stared at me through his glasses while I gawked at his perfect pencil moustache. He asked a few questions looking for the slightest sign of hesitation in me. Passing through the security took ages as the queue snaked long. The departure hall was crammed to the brim. Not a single seat was left unattended. Passengers were sitting on the floor or leaning against walls charging their phones. Someone got up, and we pounced upon his seat.

The flight was on time, and in just half-an-hour, we were approaching Paro. We didn’t get the window seat, and sat on the wrong side of the aeroplane, but could feel the tension as the aircraft began its descent. I craned my neck to get glimpses of the peaks and valleys; the aircraft approaching too close to the hills, almost grazing and skimming past them, making swift, timely manoeuvres. The visuals were breathtaking, but fun fact, Paro is considered one of the dangerous airports in the world. The runway, which is a lot shorter than its sea-level counterparts, doesn’t even come in view of the pilots until the aircraft is about 400 feet from the ground. And to top it all, are the mountains—as high as 18,000 feet—surrounding the airport on all sides.

[Click Here to watch the cockpit-view of an aircraft landing at the Paro International Airport. You can start at 4:00 minutes.]

The immigration was smooth. Indians enjoy visa-on-arrival; they can just show up with their voter card. The officials looked at each other when we said we didn’t have prior hotel reservations and filled out the hotel address on the immigration card themselves. A young woman hanging about the counter, a staff, got hold of us once we passed through immigration. She was in desperate need for Indian banknotes, which was in short supply, thanks to the demonetisation. We gladly exchanged a couple bundles of hundred rupee notes for Bhutanese Ngultrum. As the value of both currencies is equal, there was no need to use our brains.

Outside, there was no mad rush. A man approached us. He was wearing a traditional black Gho, a knee-length robe, wrapped around his body like a kimono. He inquired if we required a taxi to Thimphu. Even though we spoke in English, to our surprise, he replied in fluent Hindi. His name was Pasang. He quoted a fair price of Nu. 1600 and we didn’t haggle. It was lunchtime, and we hoped to grab a quick bite, but Pasang informed us that there was no restaurant around. It was better to wait until Thimphu.

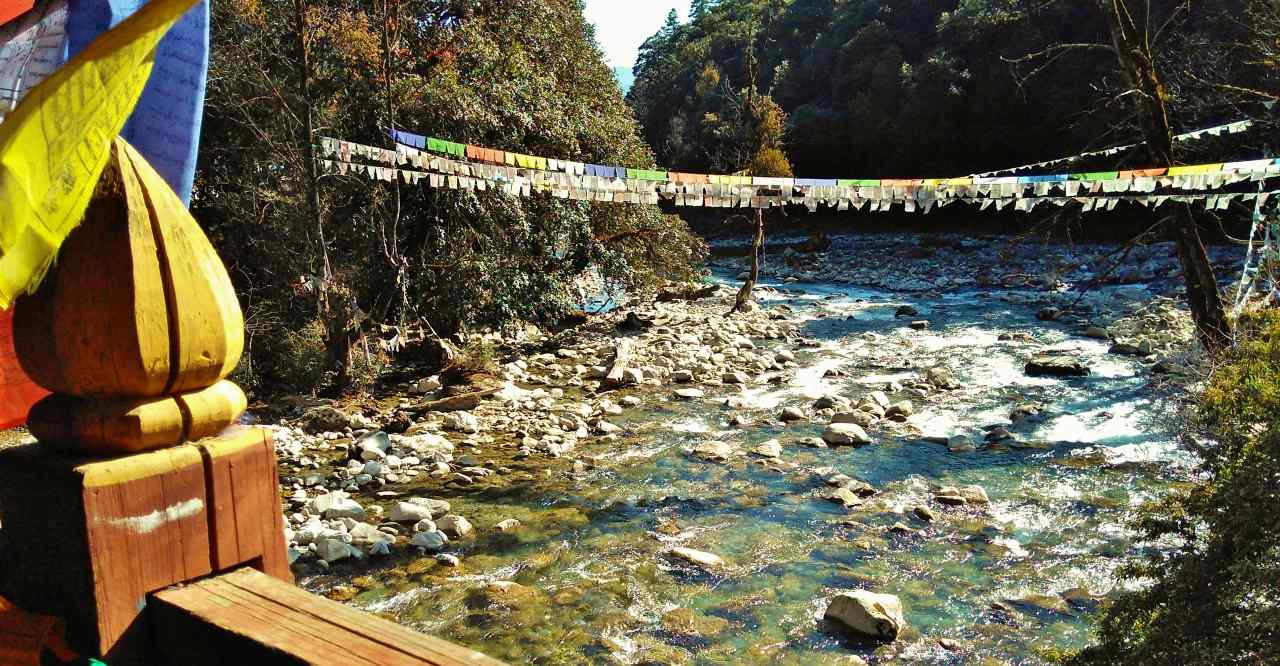

The road was smooth, winding through the mountains—green and gold. It was the dry season; the green grass-wrapped hills had turned golden. Sparkling Paro Chhu (Chhu – river) meandered alongside us, crystal clear, emerald green, frothing and tumbling past pebbles and rocks. On the hillsides, glimpses of random colourful shrines and prayer flags evoked a sense of tranquillity in us.

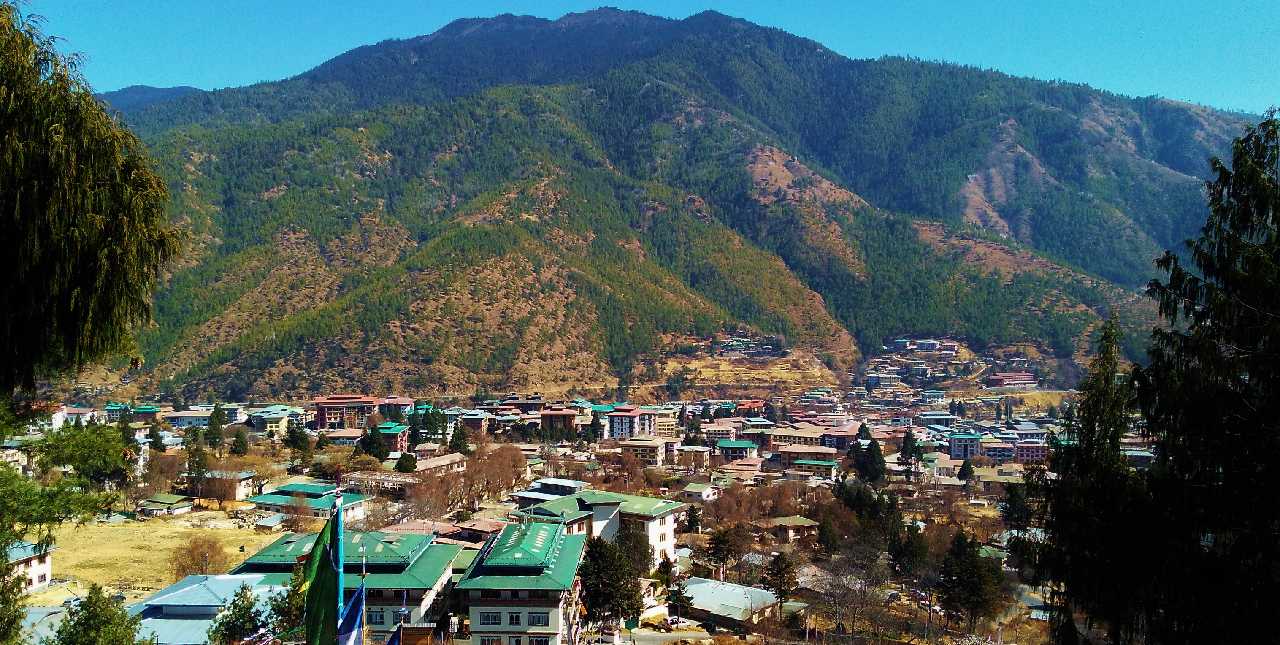

Thimphu, the capital city of Bhutan, is about 50 kilometres from the Paro International Airport. It took us just about an hour to reach there. We wanted to stay near the city centre, but Pasang’s recommendation was a hotel with dark, soggy rooms, which we humbly declined. We spotted an expensive-looking hotel and barged in, praying. And after a lot of bargaining, which my partner did, while Pasang and I exchanged embarrassing glances, she struck gold. It was off-season, and we got almost 50% off. Hotel Galingkha is located just off the world-famous traffic post on Norzin Lam 2. It is a wooden traffic post, with brightly painted motifs, where the traffic guard waves his hands with mechanical precision for the tourists to click photographs.

The hotel room had wooden floors and was equipped with—a bed that was too comfortable, a vanity table, a mini-bar, an electric kettle with complimentary sachets of coffee and tea, and large sliding windows that opened to the street, Chhoten Lam. The bathroom had a bathtub along with the usual accessories that are expected at any high-end hotel.

We ordered lunch; vegetable fried rice and chicken curry, Bhutanese style, and relished them watching the street from our window. The food was delicious; it wasn’t spicy for the number of chillies that were in it. After lunch, we freshened up and headed out. The shop beside the hotel sold sim cards, and I got one for Nu. 100. The first thing I noticed was that the shop was run by women. There were about three-four women in their traditional outfit, the Kira, an ankle-length wrap-around dress accompanied by a long-sleeved outer jacket, running the shop and watching a 90s Hindi movie on the television in full volume. It reminded me of the Khasi women in Meghalaya who manned the shops, while the men did other jobs like farming or driving taxis. The other surprise was that the cars stopped at zebra crossings for pedestrians, without a traffic signal or a traffic policeman wielding his stick and blowing his whistle.

By the time we reached Clock Tower Square, it was dark. The clock tower is a four-faced rectangular tower with a gabled roof and is carved and painted in rich traditional style with golden dragons and bright flowers. Local teenagers sat on the steps in groups, and young kids played near the tower. The shops, cafés and hotels along the eastern edge of the square had matching architectural style, with small windows and sloping roofs. A curio shop sold traditional and antique artefacts; masks, bells and gongs and something interesting—wooden phalluses. The fifteen-year in me went bananas seeing so many wooden phalluses, in all sizes and shapes. I went around giggling and pointing at them, and then stealing a quick glance at my partner, corrected my shameful act and re-examined them with the respect they deserve. Neither of us questioned the shop owner about it, and since we weren’t going to buy any artefacts—with their prices beyond our means, we escaped to an adjoining café, where locals sat around a wood-fired heater drinking tea and coffee and watching television. We ordered chicken puffs.

Later we strolled along Norzin Lam 2, the main thoroughfare of the city, bounding the western side of the Clock Tower Square. We went in and out of shops selling souvenirs; Buddha statuettes to cowbells to wind-chimes and prayer wheels, priced exorbitantly for the tourists.

We ended the night with a beef burger and a beer; listening to rich young Bhutanese men sing karaoke and smoke cigarettes. And I thought this country was a no-smoking nation. In the afternoon, Pasang had stopped his car and vanished into a market to get his daily dose of cigarettes. But when I approached a shop that sold betel leaves and areca nuts (doma), the woman looked elsewhere as if she had never heard of such a thing. It is available, sold illegally in secret pockets/shops, but not for tourists.

DAY 2: THIMPHU

Built in the 12th or 13th Century, Changangkha Lhakhang is situated on a hilltop overlooking the Thimphu Valley. The temple is a favourite among Bhutanese couples to bring their newborns for names and blessings from Tamdrin, the protector deity.

We started after breakfast—aloo-parathas with pickle and yoghurt. The weather was warm, with the sun excruciatingly bright. At these altitudes, the sun is harsh, and although it is cold, it is important to protect oneself with sunscreen and sunglasses. In the shade, however, the breeze was nippy. The distance to Changangkha Lhakhang was about two kilometres from our hotel. The walk was uphill but not exhausting as the slope was not too steep. If one takes a car, it should be a 10-min drive. But in my opinion, walking is the best way to explore a place. On the way, we came across more phalluses, drawn on walls of houses in rich gaudy colours. By this time, I had done my research, and the reason was: Drukpa Kunley—a poet, monk, saint who lived in the 15th Century, and earned monikers such as ‘The Divine Madman’ or ‘The Saint of 5000 Women’, while his penis is referred to as the ‘Thunderbolt of Flaming Wisdom’. He had his own eccentric style of demonstrating that celibacy was not an absolute for enlightenment, and the women of his time sought out his blessing in the form of sex. Today, he is the reason for the introduction of phalluses in drawings, paintings and statues, both as a symbol of fertility and to drive away the evil spirits. Chimi Lhakhang, a temple in Punakha District, which is his abode, is a temple of fertility, where women hoping to conceive visit to be blessed. However, if one considers going to the temple, do bring him a bottle of wine.

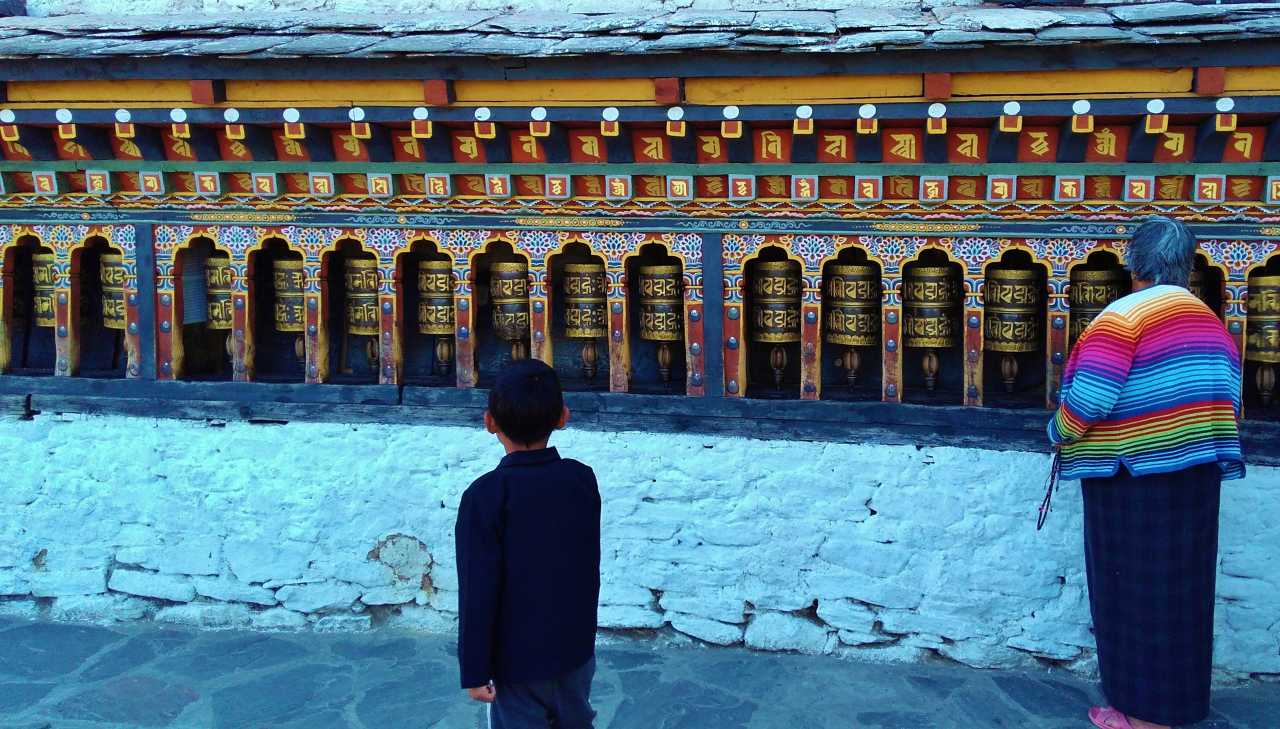

The central statue in Changangkha Lhakhang, built of bronze and plated with gold, is of Avalokitesvara, a Bodhisattva who embodies the compassion of all Buddhas. The inner sanctum was dark and smoky, with a soft scent of frankincense and butter. The outer region of the Lhakhang had a line of prayer wheels with black-gold scriptures.

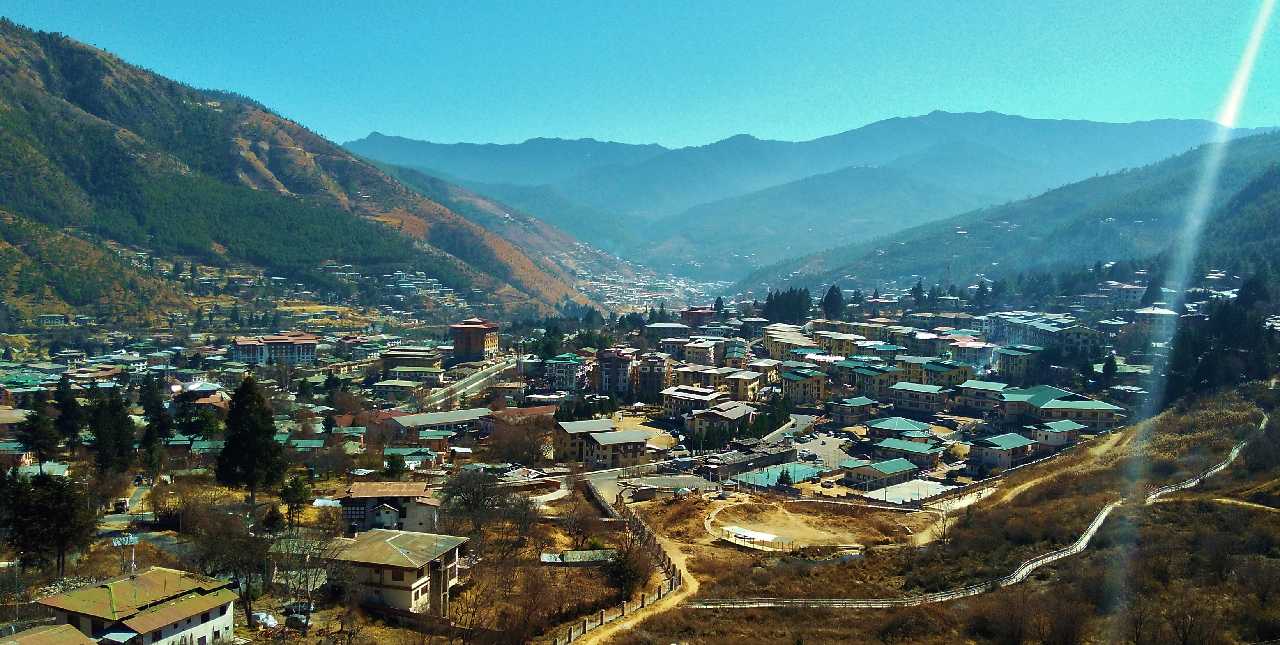

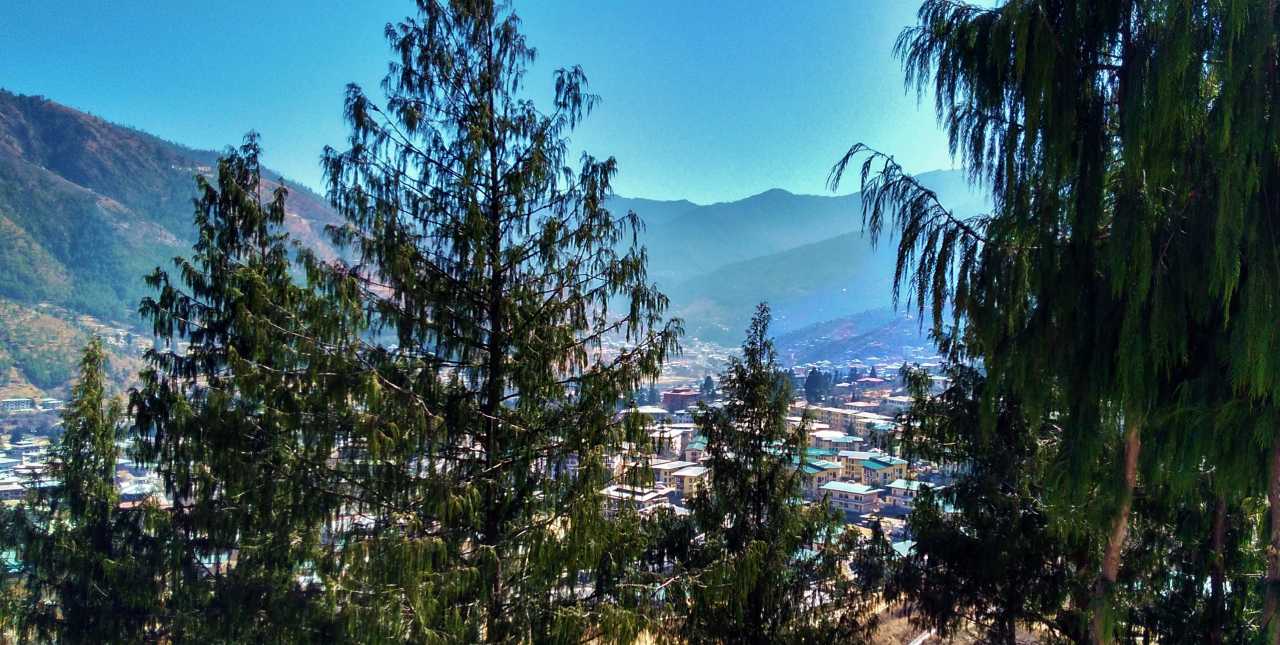

The view of Thimphu from the temple is expansive and breathtaking, and as the serenity of the temple calms you down, you sit in all humbleness and soak the moment; the monotonous drone of the monks chanting prayers and the fluttering of colourful prayer flags in your ears.

We walked back the same route—which this time took one-fourth of the duration and energy as it was downhill—and had lunch at a cafeteria on Gongdzin Lam, a street filled with supermarkets and restaurants. With our belly filled, we walked to National Memorial Chorten.

It is a Tibetan style white stupa crowned with a golden spire, built to honour the Third Druk Gyalpo, the grandfather of the present Druk Gyalpo (Dragon King), His Majesty King Jigme Khesar Namgyel Wangchuck. The space was crowded—kids running around, families seated in knots on the ground surrounding the Chorten, while the path leading up to the structure was lined with tired elderly leaning against the rails. A local was feeding a flock of pigeons. Others were circumambulating the structure, ending at the giant prayer wheels located at the left of the premises. On our way back, we stopped at the Swiss Bakery located just behind our hotel—that my partner had been eyeing from our hotel window since our arrival—and packed a few patisseries and cakes.

In the evening, we headed east towards the river, Thimphu Chhu or Wang Chhu along Drentoen Lam, past the General Post Office, and continued along Dungkhor Lam towards the Centenary Farmer’s Market. On the way, we passed markets, selling clothes, toys and electronics to vegetables and meat.

We crossed the river along a covered wooden footbridge to reach the Riverside Market. The market is a labyrinth of stalls that sold handicrafts, mostly souvenirs and garments. The afternoon light was fading, and the stalls were shutting down. Most of them were closed anyway. When we inquired, we learned that since it was off-season for tourists, the owners had gone back to their villages to spend the winter with their families. Come spring, and they would return. From one of the stalls, I purchased a green woollen cap for a fair price.

We continued along Chhogyal Lam, the easternmost street of the city, with the Thimphu Chhu flowing beside us, clicking selfies sporting my new woollen cap. Upon discovering a 45-foot tall statue of Buddha, we briefly entered the Centenary and Coronation Park, opposite the Changlimithang Stadium, and as the evening rushed upon us, we returned to our hotel.

DAY 3: A TREK TO CHERI MONASTERY

The previous evening, I called Pasang and asked if he could take us to Cheri Monastery the following day. He said he was already engaged and offered to send his brother instead. His brother, Namgay arrived on time in his red Maruti Alto. Namgay was a big man; tall and plump, but with gentle manners. He resembled nothing like his dapper-looking brother, and we figured that he was probably a cousin or something. He was wearing a chequered maroon-cream coloured Gho. In our first interaction, we realised that he understood no English and only a smattering of Hindi. He was a simpleton, more suited to the rural environment.

We needed a permit to visit Dochu La the following day, and when I asked if I could get it tomorrow, Namgay pondered for a while and conveyed that we also needed a permit to visit Cheri Monastery. So we headed to the office of the Department of Immigration. Anyone arriving at Paro Airport is initially given a permit valid for a week to visit the districts—Paro and Thimphu. If the person wishes to visit other places or extend his stay, he is required to get a fresh permit from the Department of Immigration office located near the Chubachu Traffic Circle on Norzin Lam 3. Upon reaching there, Namgay stood by his car and pointed us to the small office which issued the permit. The process was swift and was completed within half-an-hour.

Namgay inquired if we had visited the regular tourist attractions, and when we shook our heads, he seemed surprised. He suggested that we at least see the Buddha on the hill. Soon we were climbing up a hilltop overlooking the Thimphu Valley. The statue of Buddha Dordenma is of gigantic proportions. It is not only one of the largest statues of Buddha in the world but also holds inside itself over a hundred thousand figurines of Buddha, which like the main one, are all made of bronze and gilded in gold. The base on which the Buddha sits is a meditation hall.

It was indeed beautiful, and if not for Namgay we would have missed such a remarkable sight. Namgay was happy; he smiled, and for the first time, revealed the secret to his taciturn nature. He had packed a mouthful of doma or areca nut in his mouth.

About fifteen kilometres north of Thimphu, located are the twin monasteries of Tango and Cheri on two separate hilltops. To reach the monasteries, one has to hike uphill. Both the hikes take about an hour to complete, and the effort is comparable. So, we had to decide, and we chose Cheri Monastery. But, before that, Namgay looked confused. He wasn’t sure if he was heading in the right direction. He drove haltingly, like someone learning to drive, until he decided to take my advice and stop and ask for directions from a pair of monks crossing our way on foot.

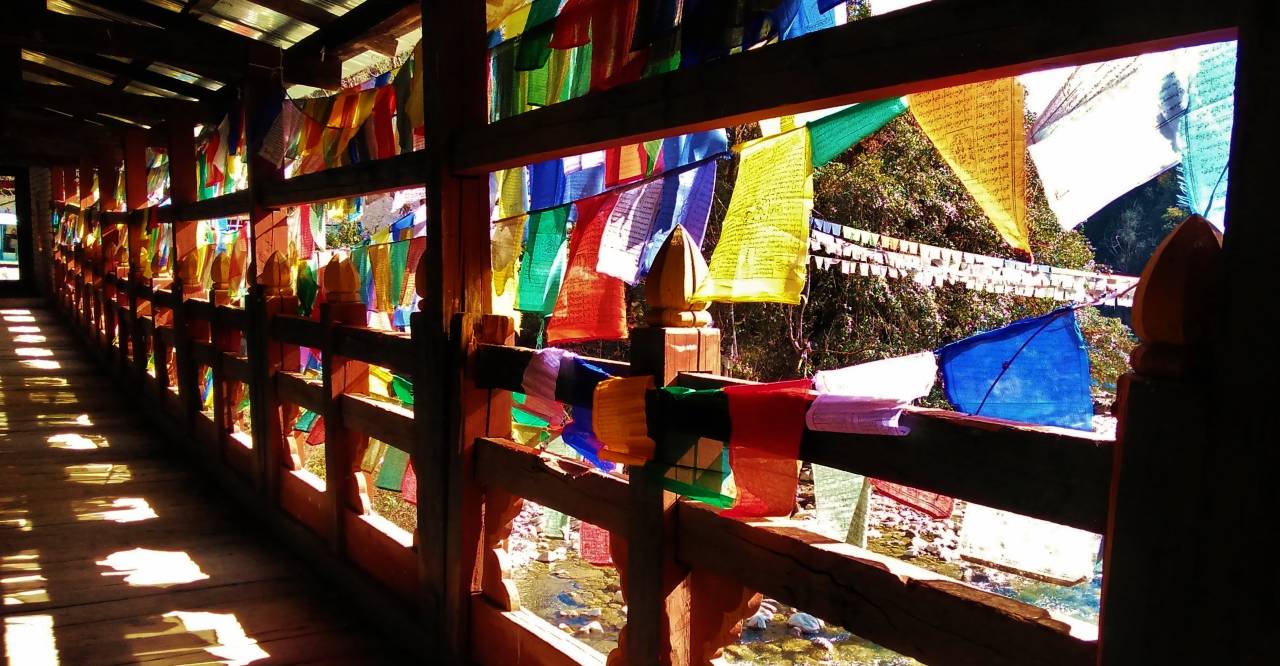

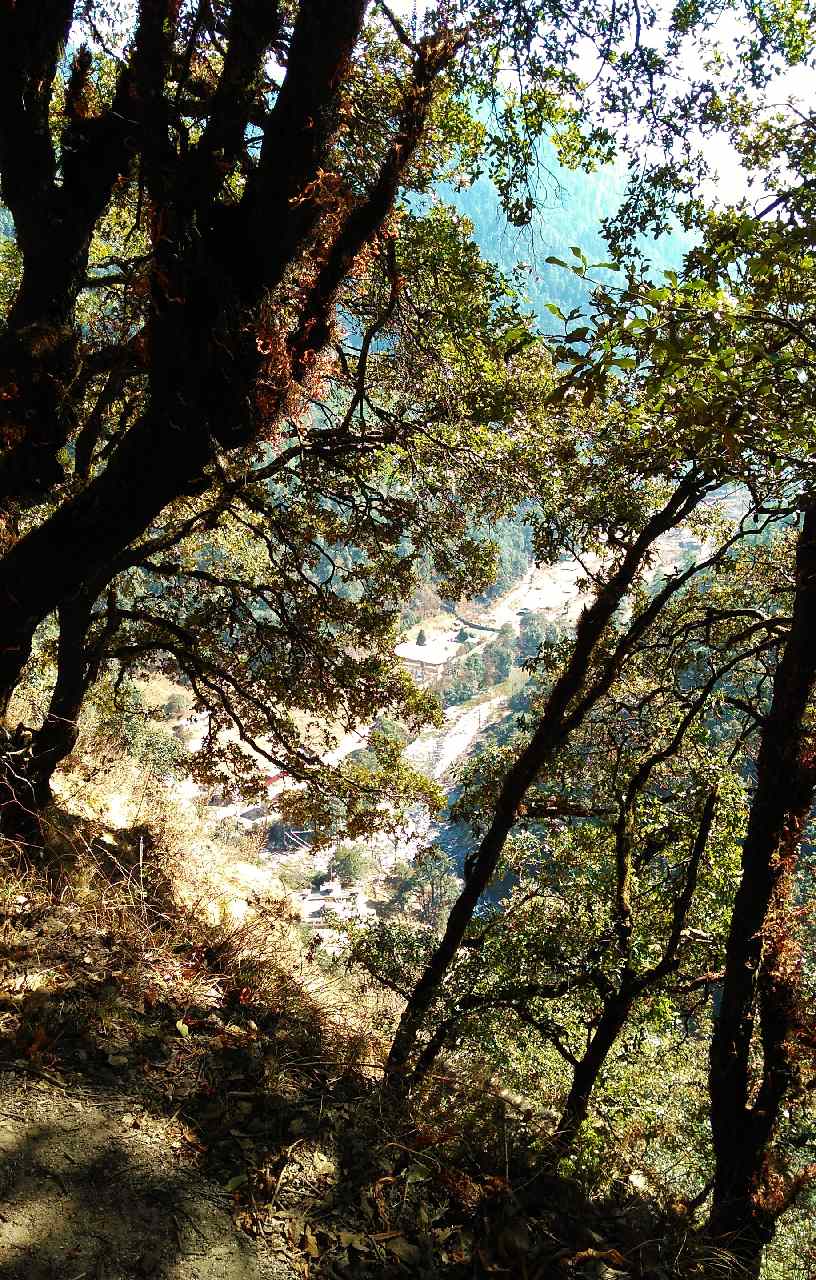

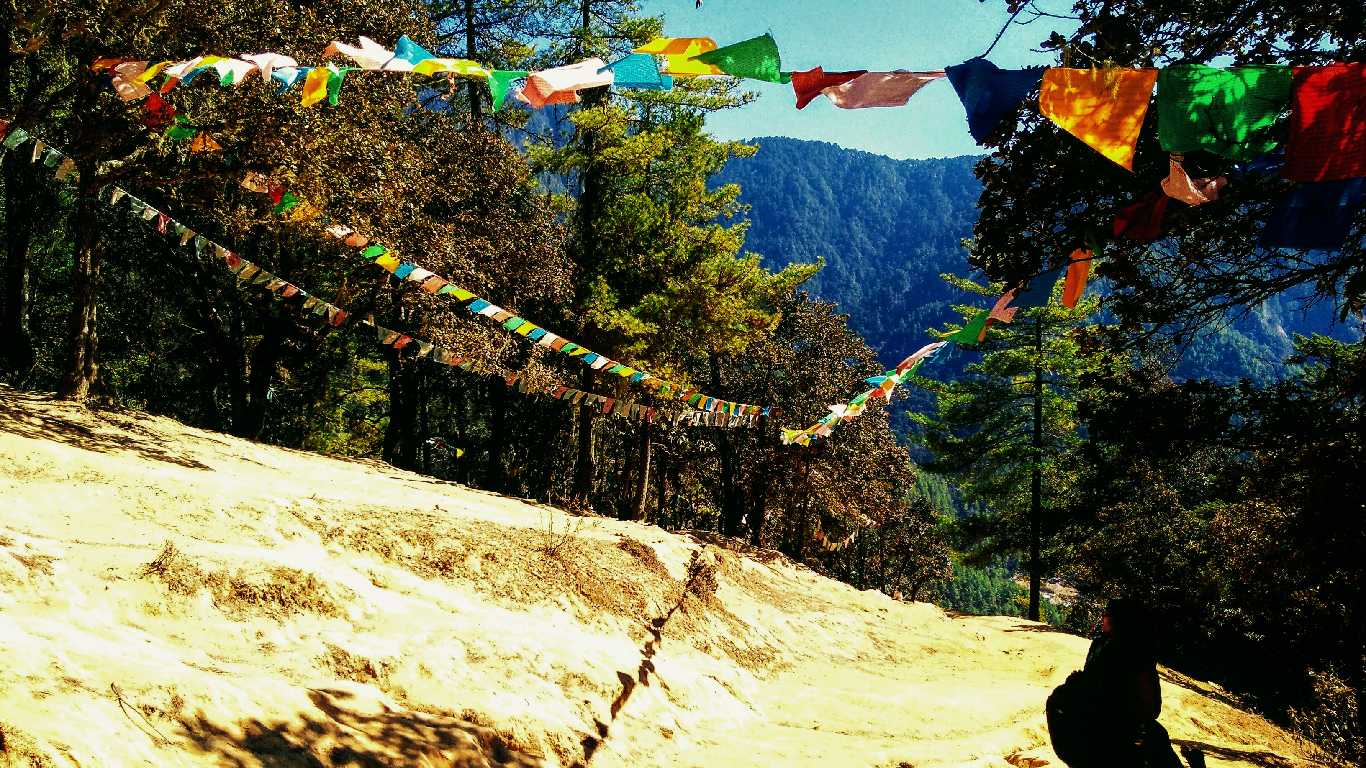

On reaching the starting point of the hike, Namgay showed us to a wooden footbridge over the Thimphu Chhu. We crossed the wooden bridge strung bank to bank with prayer flags, and proceed past a shrine, through the forest, along a dirt trail winding up the hill, speckled with sunlight. It was moderately steep, and we paused at intervals to catch our breath and see the valley below. A few tourists, mostly backpackers crossed us, heading downhill.

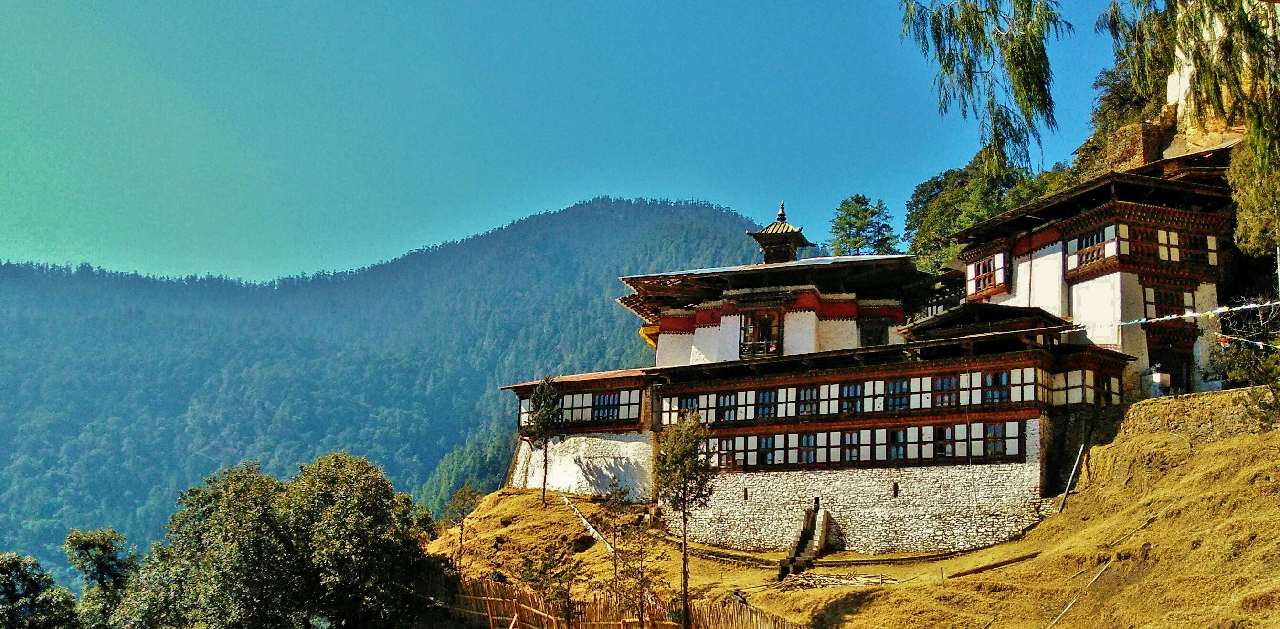

The Cheri Monastery, better known as Chagri Dorjeden Monastery was established in 1620 by a Tibetan Buddhist Lama named Ngawang Namgyal, the first Zhabdrung Rinpoche, who brought together warring fiefdoms and unified Bhutan into a nation-state. He also created a separate Bhutanese identity, distinct from their Tibetan cousins. Today the monastery serves as a great learning centre of a particular school of Tibetan Buddhism.

On our return, Namgay was missing. He was not in his car, and we looked everywhere, questioned other drivers, but he had indeed vanished. We didn’t have his phone number. So I rang Pasang, whose wife picked up the phone, and then Pasang called me to get the facts right, and about fifteen minutes later, Namgay emerged from the bushes, in all smiles. He was doing something by the riverbank. We didn’t ask him, nor did he explain, and all of us, like mature adults, let it slide.

Namgay now over-compensated, by pointing at various hills and shrines and describing them the best he could. He showed us a guarded compound and said that the king lived there—Dechencholing Palace. When we asked if we could visit, he furiously shook his head and said, ‘No permission!’ We paused briefly to see Tashichho Dzong, the seat to the country’s government from afar, and then returned to our hotel.

Namgay left us after promising to take us to Dochu La the following day, and we headed up a narrow dim-lit staircase to a restaurant across our hotel—Zombala 2 Restaurant. It had good reviews online, that promised great food at an affordable price, but I was sceptical about the reviews. The restaurant was on the first floor, and we took a seat by a window, but still, it didn’t change the fact that it was dark and dim-lit. We ordered chicken noodles, chilly chicken and Ema Datshi, which by the way is the national dish of Bhutan. Ema means chillies, and Datshi means cheese. The dish was exactly that, and from the first spoonful we took, it didn’t go down well. The other preparations didn’t fare better either, and we struggled to get them down our throat, exchanging awkward glances with the King, the present Druk Gyalpo, framed on the wall.

In the evening, after the disappointing lunch, we went to a café across our hotel—The Art Café; a modern cafeteria with tastefully designed interiors, and grabbed an egg-puff and a portion of apple pie. We also packed a couple of pastries for later. We then went down to Chang Lam, the road that flanked the western edge of the Changlimithang Stadium. We walked north; past vacant basketball courts, and found a place where a sale was going on. We purchased a few sweaters for ourselves and our family members back home, and had a sandwich and cheesecake at Coffee Culture, a café on the same side street. We continued to explore Chang Lam, lined with hotels, restaurants, cafés, pubs and karaoke bars. We ended the evening at The Zone with fish & chips, roast chicken, and a bottle of unfiltered, local wheat beer—Red Panda.

DAY 4: DOCHU LA

We woke up late, for the street dogs had kept us awake all night. In the morning, they are the cutest little bundle of joys roaming around, walking up to locals and wagging their tails in delight. But as the night deepens, they turn into these monsters who keep barking at the top of their voices, giving tourists sleepless nights. Thimphu is infamous for these creatures.

Namgay arrived on time. He dusted the seats of his car, cleaned the windshield, and played with a street dog. I waved at him from our hotel window while having breakfast, and he nodded back. He lived in Paro and drove to Thimphu everyday carrying commuters who worked in the city. In the evening, he returned back, collecting the same. In the meantime, he had tourists like us, or else drove around like a regular taxi.

We started after breakfast. Dochu La is about an hour from Thimphu, en route to Punakha. One has to stop midway at a checkpoint to show the permit. The drive was pleasant, and we arrived at Dochu La around half-past eleven.

Dochu La is a mountain pass at an elevation of about 10,000 feet. On a clear day, one can witness the snow-clad peaks of the Himalayas to the east of it. The pass is notorious for its weather, and stays mostly foggy, leaving the tourists disappointed. But in winter, the skies clear, and the snow-clad peaks glitter in the distance. Namgay pointed to us that the mountain range looked like a sleeping Buddha. We agreed so as not to hurt his sensibilities. There was a hand-painted information board depicting the mountain range; Jigme Singye Wangchuck Himalayan Range, the peaks as seen from the pass with their heights mentioned. Mt Gangkhar Puensum topped the chart with 7,564 m, followed by Mt Tari Gang at 7,304 m. Mt Gangkhar Puensum is not only the tallest mountain peak in Bhutan, but is considered the highest ‘virgin-peak’ in the world for it has never been summited.

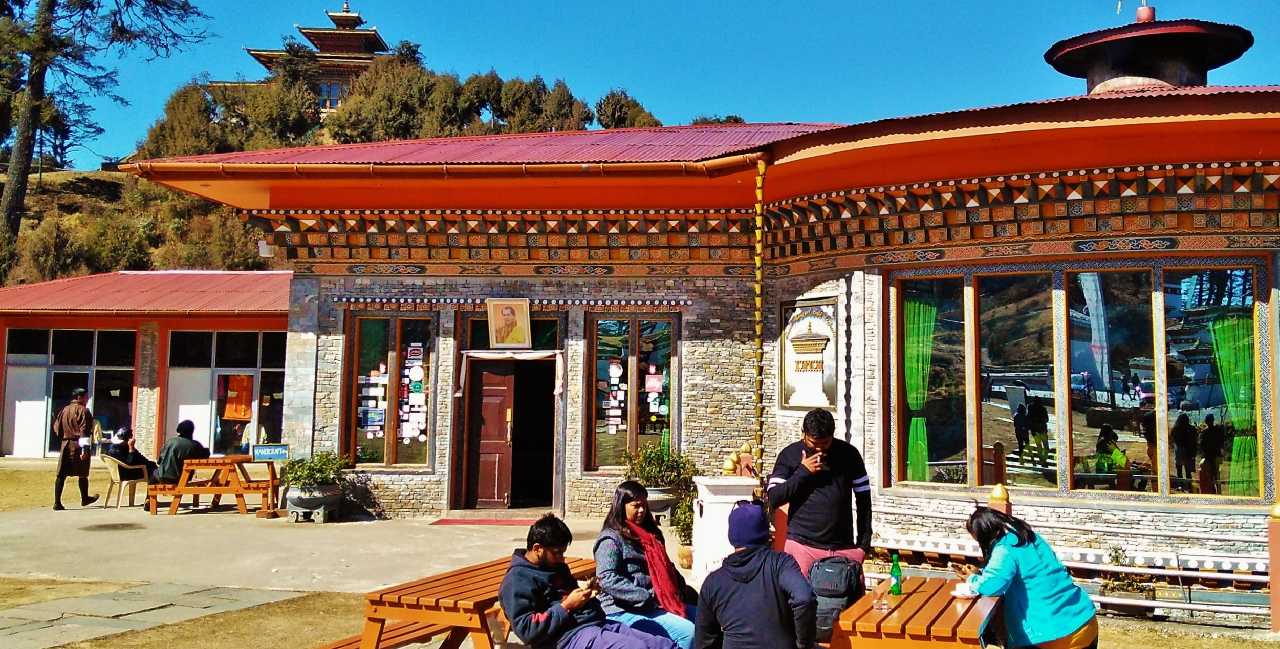

Namgay asked us to order lunch at the Druk Wangyel Cafeteria as soon as we reached; since it would take them a while to prepare. It was the only café around, and I guessed that it was run by the government. Namgay also told us to mention his presence as the café would provide him with free lunch. The interior was modern, with large glass windows to provide an unobstructed view of the snow-clad mountain range. We ordered a simple meal of rice, dal, chicken curry and potato chips. There is also a souvenir store adjoining the café, but the commodities are exorbitantly priced.

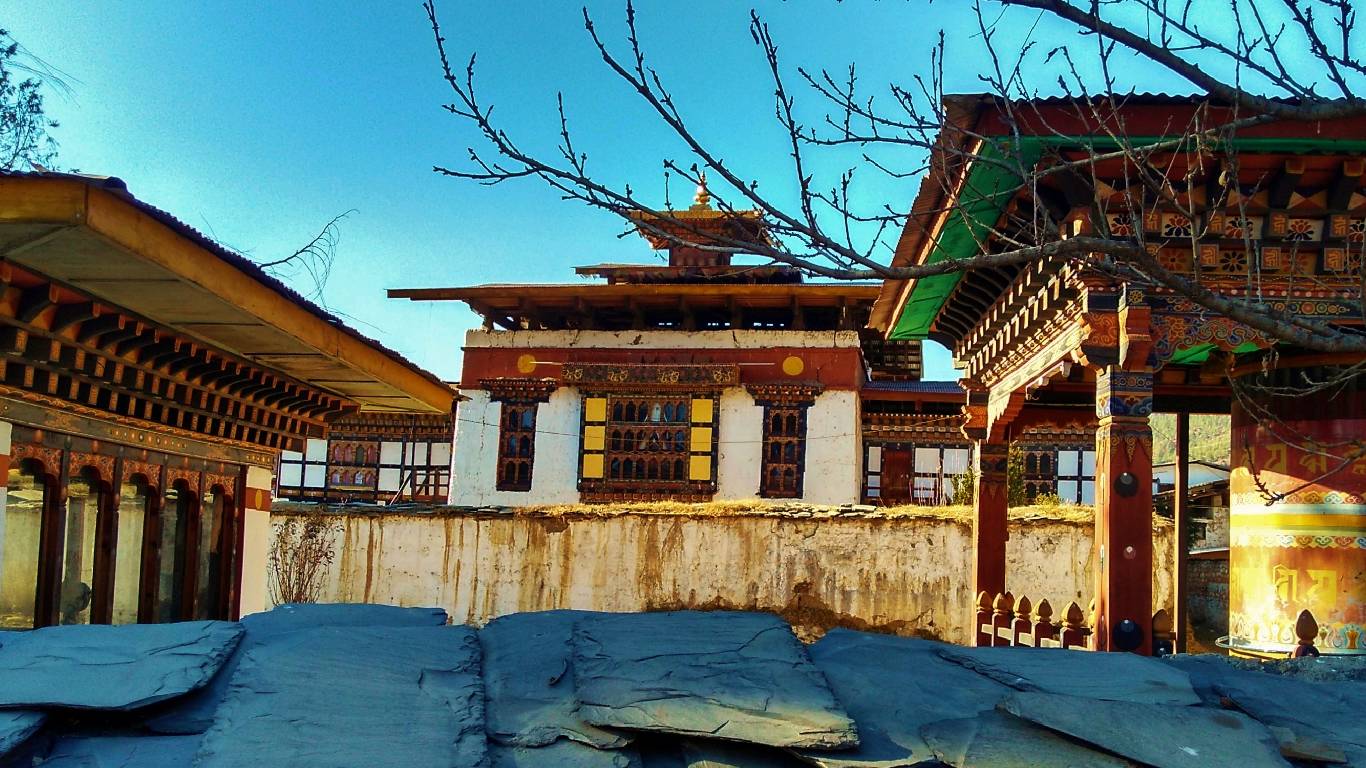

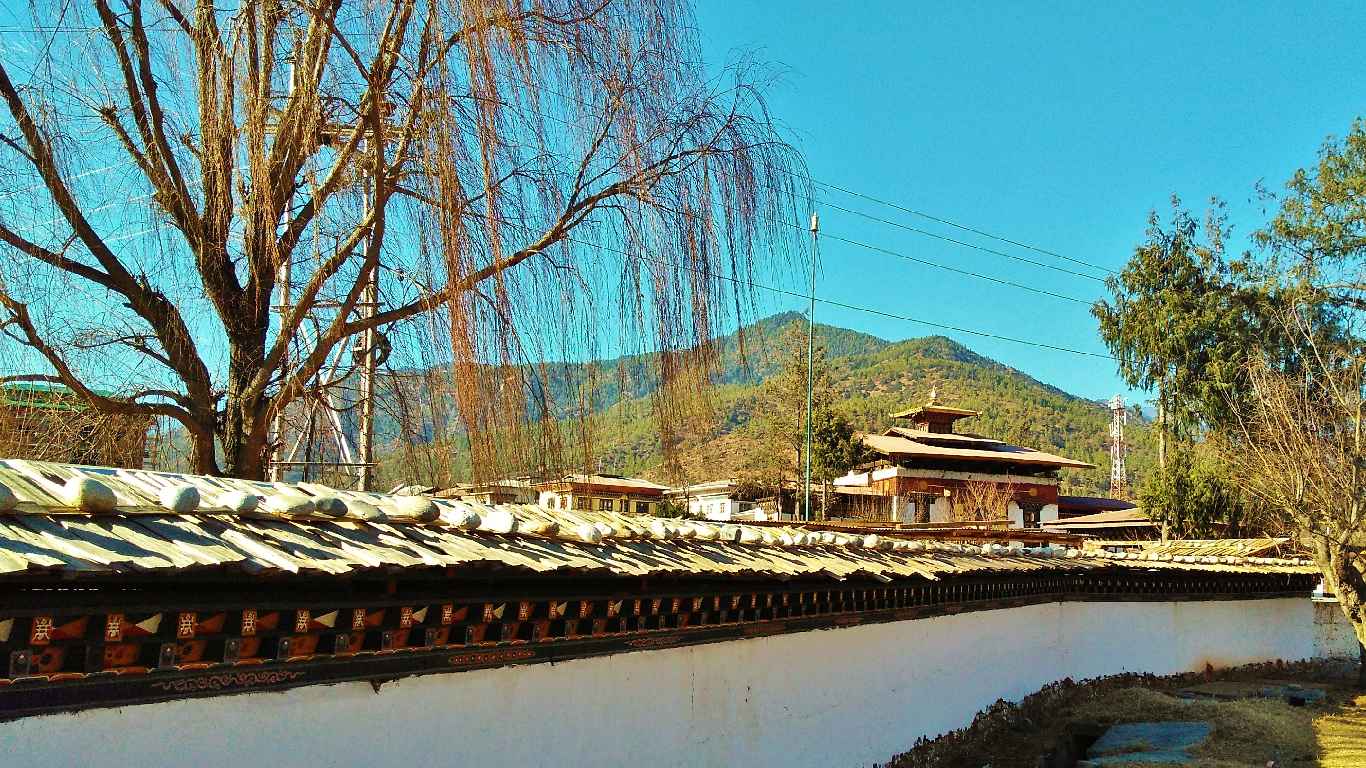

As the highway to Punakha meanders down the pass, there stand two hillocks on either side of it. On one is the Druk Wangyal Lhakhang, completed in 2008 to celebrate a century of the Wangchuk Dynasty in power, from the first Druk Gyalpo, Ugyen Wangchuck to the fourth, Jigme Singye Wangchuck, who had by then abdicated his throne in favour of his eldest son, Jigme Khesar Namgyel Wangchuck. Inside the Lhakhang, wall murals depict a fusion of traditional and modern themes; with aeroplanes and laptops entwined with the ancient motifs.

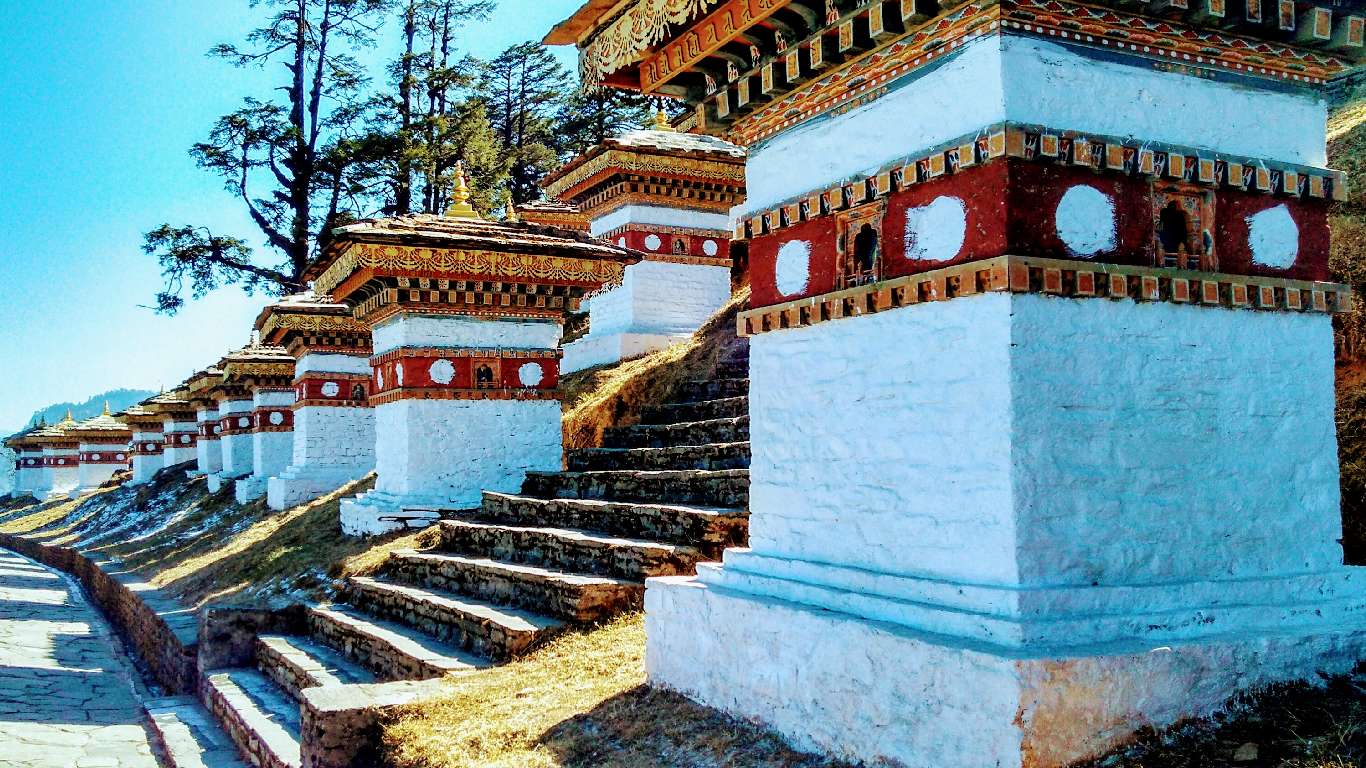

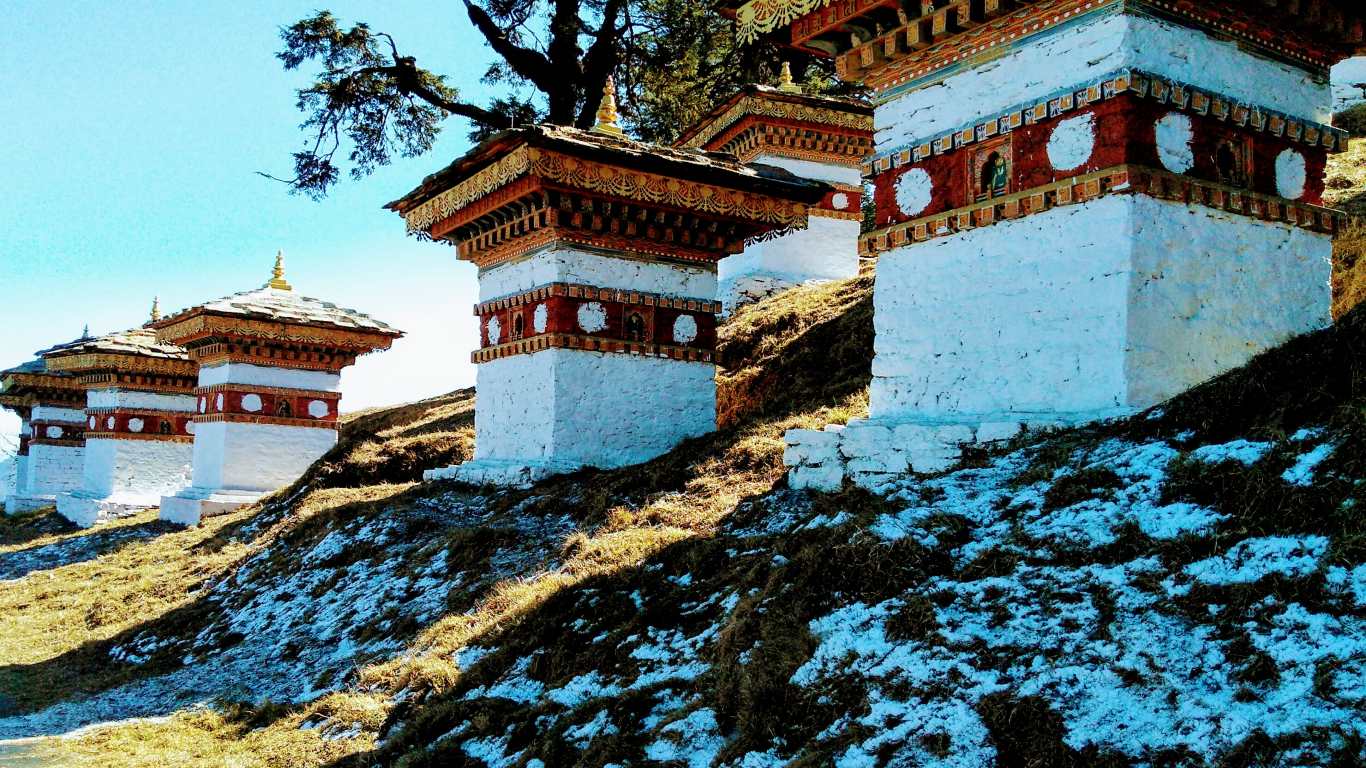

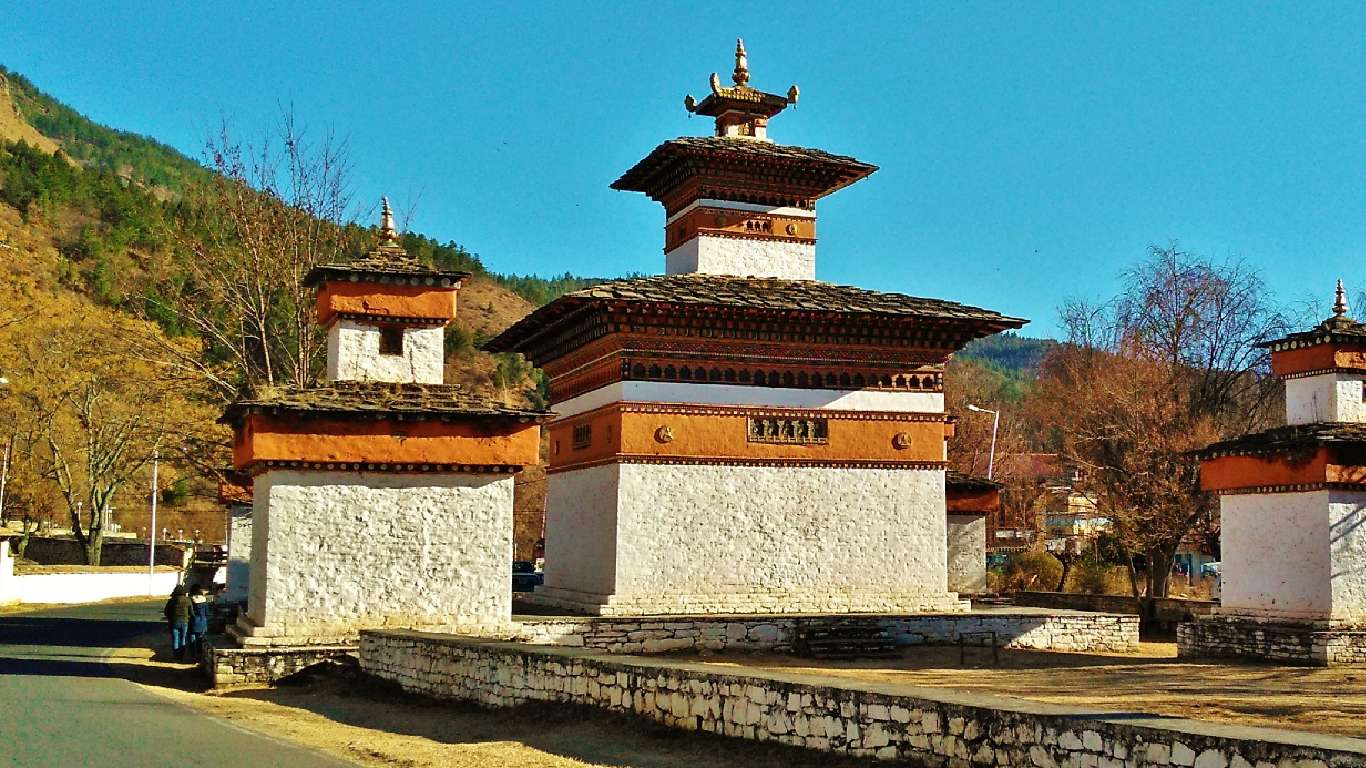

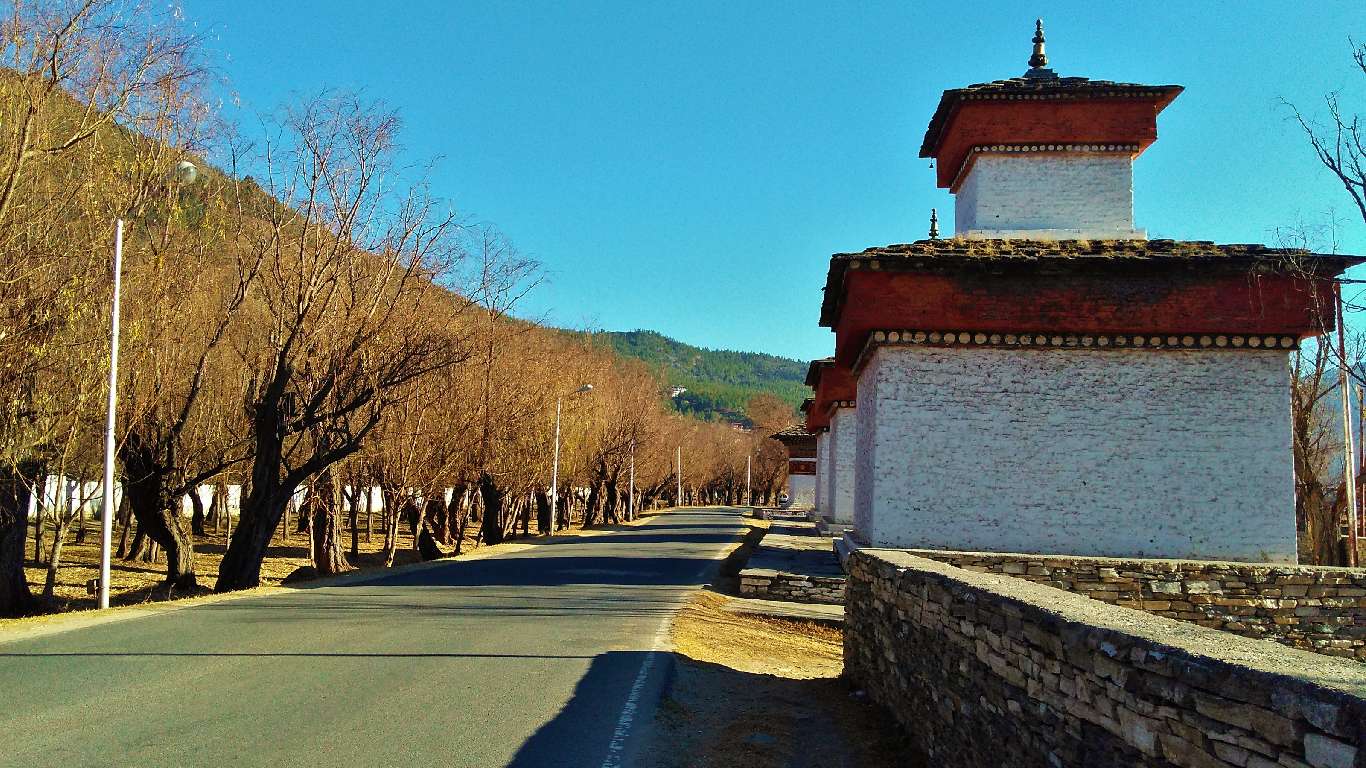

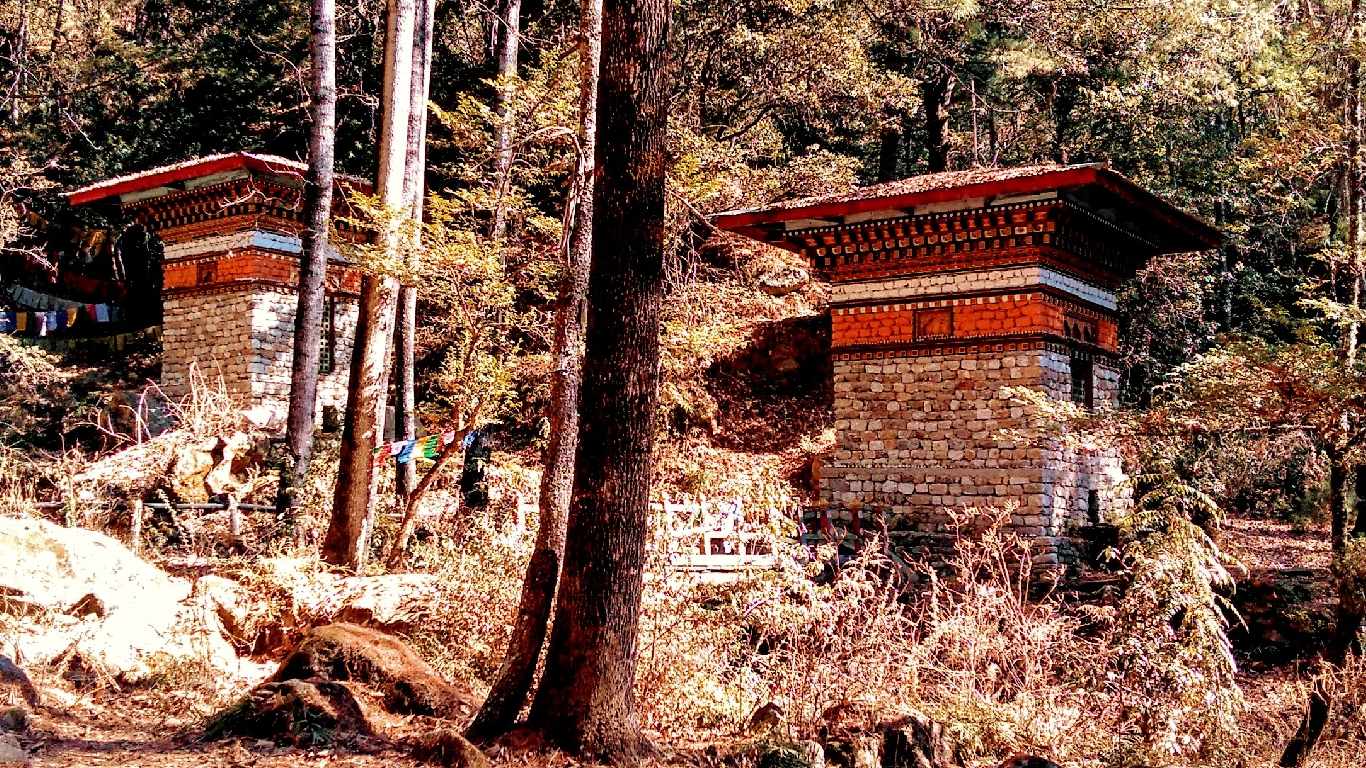

On the other hillock, stands 108 Chortens, known as the Druk Wangyal Khang Zhang Chortens. They were built under the patronage of the Queen Mother Dorji Wangmo, the eldest wife of the former king, Jigme Singye Wangchuck, after his victorious campaign against Assamese insurgents in 2003. The chortens were built to honour the martyred Bhutanese soldiers who died in the campaign. The locals call them ‘the chortens of victory’.

After our simple but delicious lunch at the cafeteria, we roamed about the chortens and sat on the slopes that had collected snow the previous night. Surrounding a principal chorten on the top of the hillock smaller chortens descend down in three layers. The topmost layer has twenty-seven chortens, while the subsequent layers have thirty-six and forty-five chortens, respectively.

On our way back, we dropped by Simtokha Dzong, a fort turned into a monastery. It was built in early the 17th century by Zhabdrung Ngawang Namgyal, the person I had previously mentioned as the unifier of Bhutan. The main Lhakhang houses a large image of Buddha with eight bodhisattvas on its sides. There are also beautiful mural paintings on the walls, considered one of the oldest in the kingdom.

On returning to the city, we asked Namgay to leave us at the Clock Tower Square. We spent our last evening in Thimphu, lazily sitting on the steps of the square and moving between the souvenir stores. I ended up purchasing a statuette of Buddha made of red stone. Presently, it sits blissfully on my work desk, reminding me to calm down; breathe… and not lose my own self in the rat race we have made our lives to be.

DAY 5: PARO

We checked out of our hotel after breakfast, and en route Paro, stopped at the Chhuzom Bridge to see the confluence of the Thimphu and Paro Chhu—a sacred site for the locals. Namgay told us that it was like the union of Father and Mother, where Paro Chhu, often known as Pho Chhu is the father and Thimphu Chhu, the mother.

We arrived at Paro just before lunchtime. Paro is about 52 km from Thimphu, and the valley sits at a similar altitude as Thimphu Valley. Namgay took us to Hotel Seasons. It was a budget hotel, and after taking a look at the room, we checked in. The room was cosy, but a little cold, thanks to the marble flooring. We dumped our luggage and went to the restaurant. The restaurant served only vegetarian food, and we ordered an uncomplicated meal of rice, dal and mixed vegetables. The food was delicious; simple, home-made. There was a group of Bhutanese women of all ages watching Indian television soap opera and snacking on Lays, cakes and apples. They offered us some.

After lunch, we set out for Rinpung Dzong just across Paro Chhu. On our way, we met Namgay at the taxi stand. He smiled and acknowledged us with a nod, happily chewing doma (betel leaves and areca nuts). Just beyond the taxi stand, at an enclosure that seemed like a sports club, men were practising archery, the national sport of the country. We stopped for a while to watch them hit the bull’s eye, but both, them and us, seemed to be out of luck. Anyway, as the afternoon light was fading fast, we continued on our journey towards the Dzong.

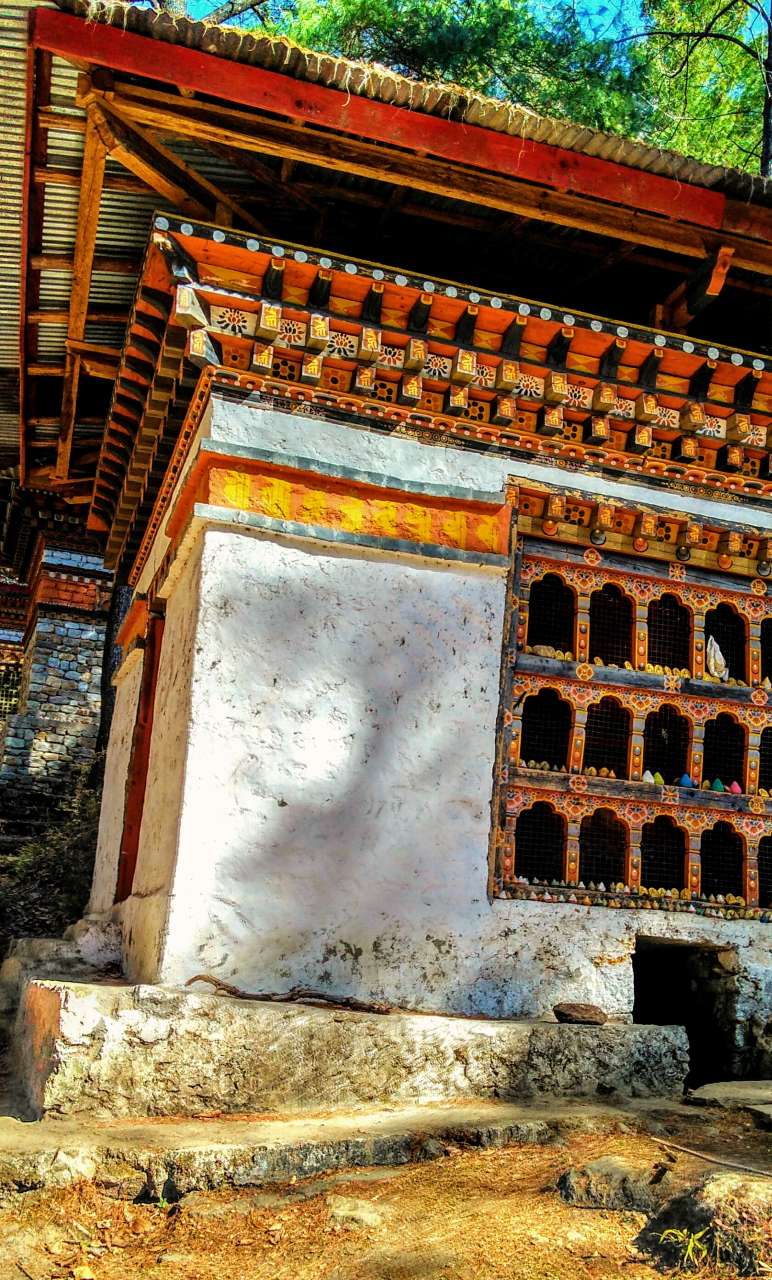

Rinpung Dzong sits on a crag just across the Paro Chhu. It is not only a monastery, but also houses the government administrative offices of the district. A traditional covered wooden bridge called Nyamai Zam spans the river. A local informed us that the bridge was not the original one, but a replica of the old one destroyed in a flood in the late 1960s. He went on with the history of the Dzong—saying that initially a small temple was set up there by a Lama, which was later converted into a Dzong. ‘But that Dzong is not this one,’ he said. The new one was built by Zhabdrung Ngawang Namgyal after he dismantled the old one in the mid-17th century. The way the man was going on, I began to wonder if he had hired himself as our guide. But my fears subsided, when he smiled, waved us goodbye, and headed towards a building across the street.

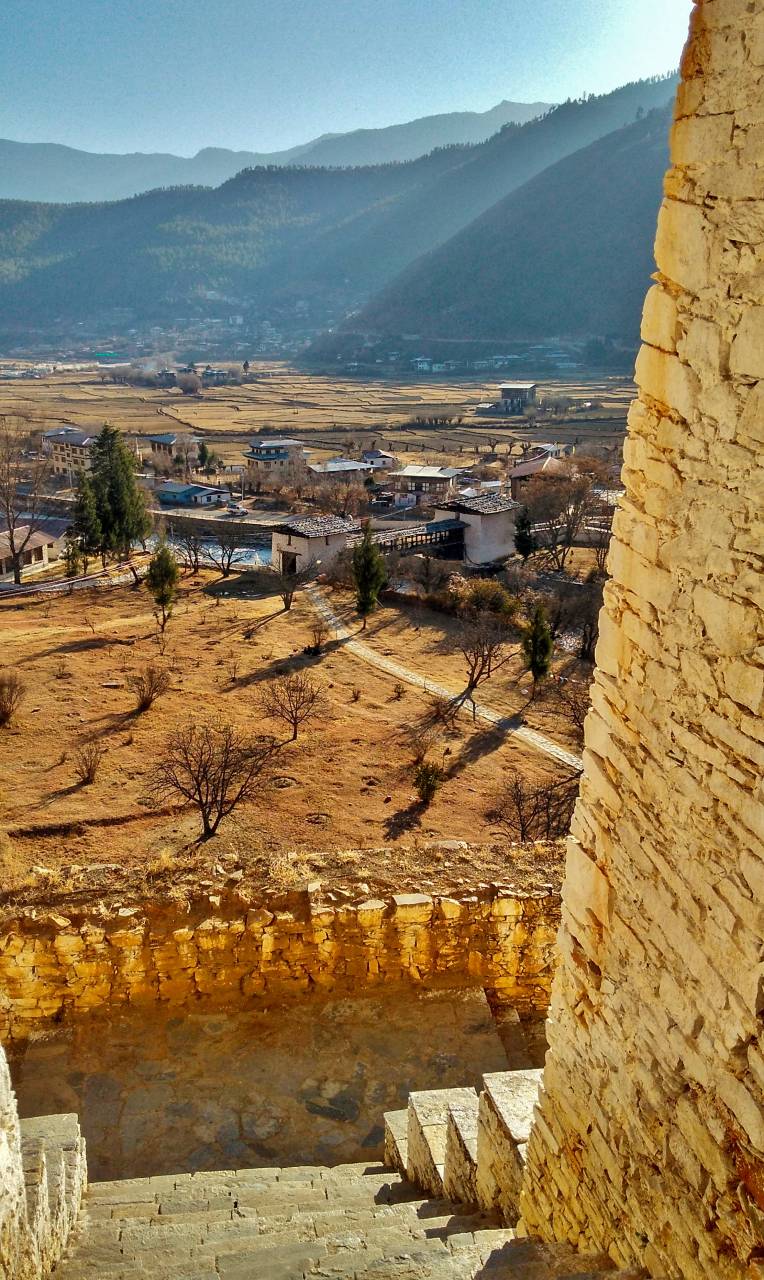

We crossed the bridge and proceeded along a paved path towards the Dzong; an imposing structure seated on a hillock, overlooking the valley. The stone steps were steep, and we climbed past a couple of smiling young monks in saffron robes with smartphones in their hands, onto the ramparts of the Dzong. We roamed about the ramparts but hesitated to enter the main enclosure as the door was shut. There was nobody around to ask if was closed, or if there was an entrance elsewhere. Anyway, it was getting dark, and we walked down the steps and headed towards town.

Later we learned that there are fourteen shrines inside the Dzong, and on the hill overlooking it, is a watchtower-fort—Ta Dzong, now converted into the National Museum of Bhutan. Every Spring, an annual festival, known as Tshechu, is held in the Dzong, which involves traditional mask dancing and retelling of mythological stories for several days.

We spent the evening inside souvenir stores along the main street. The prices were lower than that in Thimphu. The shops began to shut down at around seven o’clock; the town is small, and it does go to bed earlier than Thimphu. The weather too was colder than what we had experienced in the capital. It was perhaps just a couple of degrees above zero, and the breeze that blew across the valley, cut sharply, stinging onto our faces. In search of warmth, we went into an eatery and concluded the day with cheese pizza, carrot cake and peach ice-tea at the joint aptly named—Authentic Pizza.

DAY 6: TIGER’S NEST

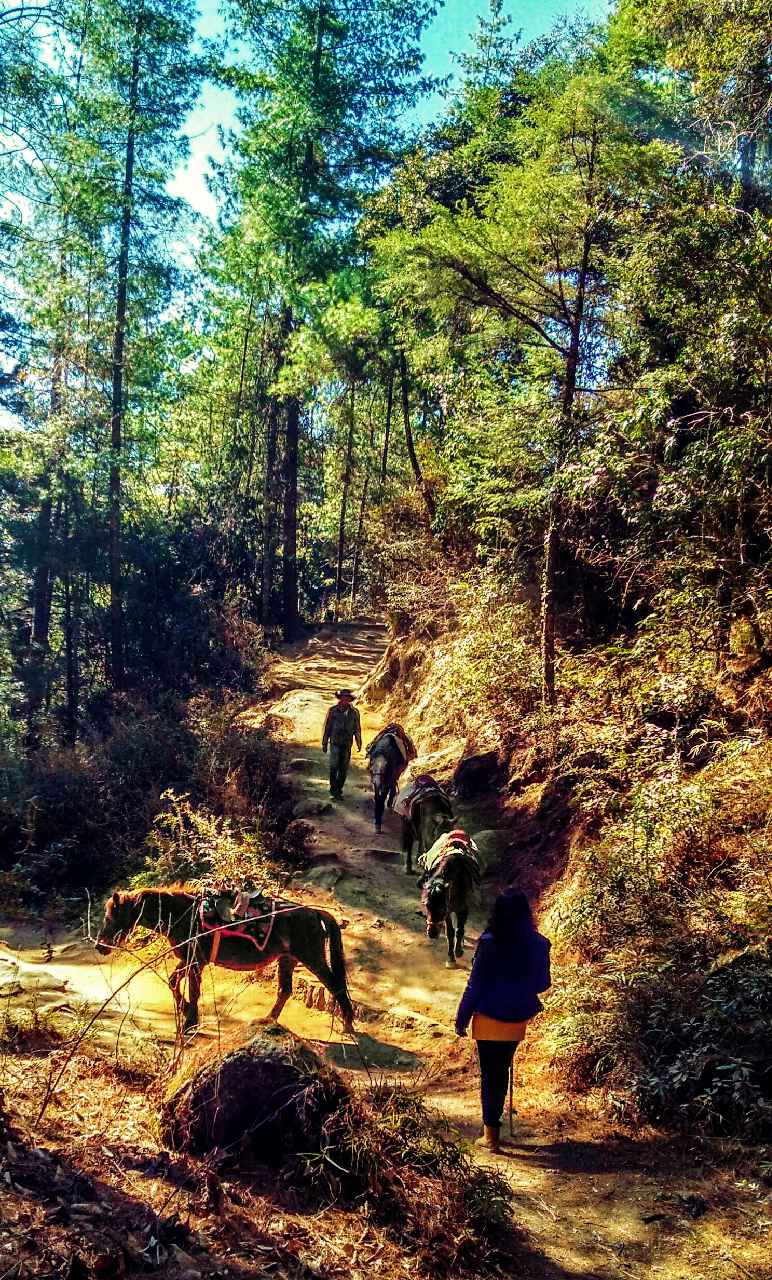

Namgay had advised us to start early, but we were late. By the time we reached the base to begin our the trek to Tiger’s Nest or Paro Taktsang, it was already 10 o’clock. A woman with a couple of horses tried to persuade us by asserting that the hike was treacherous and that it would be utterly impossible without the service of her horses. But we ignored her and proceeded after renting a couple of walking sticks. Those who are planning to take a horse, do keep in mind that they carry you only half the way, and the remainder of the trek, the most strenuous part, has to be covered on foot.

The hike is about three kilometres one way. On the internet, various blogs promise that it takes only a couple of hours to reach the top. Well, for that to happen, you need to have the endurance of an athlete and race the entire way to the top. Bear in mind that the whole trip to the top and back with a break of about half-an-hour for lunch takes at least six to seven hours to complete.

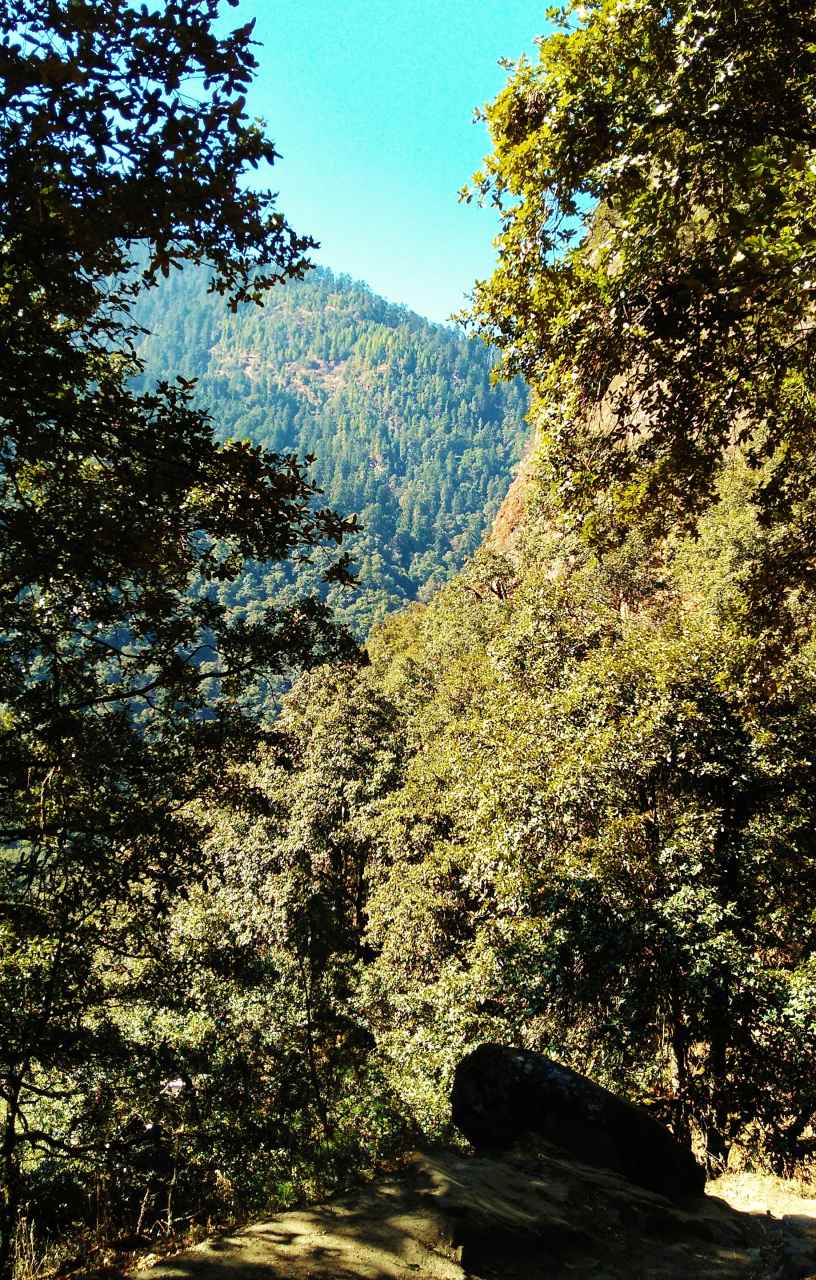

The trail through the pine forests was breathtaking, and we took our time. We paused to take photographs, and have snacks on the way. The horses carrying old people, and some young ones, passed us, skirting the edge of the cliff, pooping all the way. As the sun reached above us, and it began to grow warmer, we stuffed our woollen caps and mufflers in our backpacks. There are no shops or cafés on the way, except for one mid-way, the point till where the horses go.

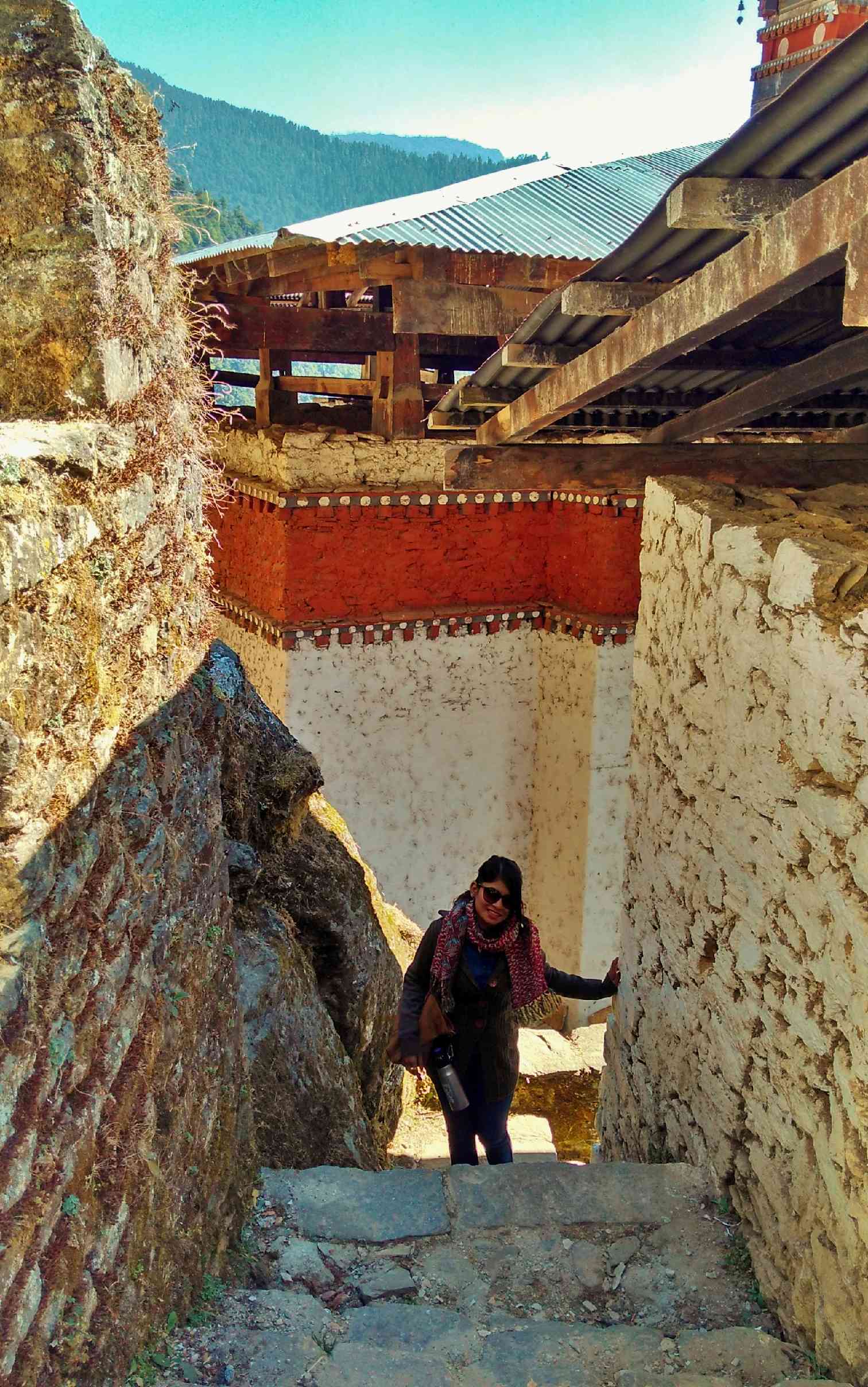

It was just around noon when we reached the top of the hill, only to discover that we have been climbing the ‘wrong hill’ all along. The monastery was hanging precariously onto a cliff on the other hill, and we were now supposed to take a steep stone staircase down, cross a bridge over a frozen waterfall, and climb another set of stairs to reach the monastery. I wondered if it wouldn’t have been wiser for the monks to carve a path in the hill where the monastery was. But given the shape of that hill, with almost vertical rock slopes, I realised that it would have indeed been a challenge.

As we sat pondering about the decision of the wise lamas, someone informed us that we needed to hurry as the monastery closes an hour for lunch at one o’clock. We dashed down the staircase and climbed another set of stairs to reach the monastery just in time, panting, out of breath.

Tiger’s Nest, locally known as Paro Taktsang, was built around the end of 17th century where Guru Padmasambhava is said to have meditated about ten centuries ago. Padmasambhava is worshipped as the second Buddha in Tibet, Bhutan, Nepal and parts of India, as many consider him a direct reincarnation of the Buddha, as foretold by the Buddha himself. He is also said to have introduced Buddhism in Bhutan and is the patron deity of the kingdom. The legends recount that Padmasambhava flew from Tibet on a tigress’s back to this site, where he meditated for four months. The tigress was none other than Yeshe Tsogyal, the former wife of the Emperor of Tibet, turned follower of Padmasambhava. Some schools of Tibetan Buddhism consider her as a female Buddha since she had attained enlightenment in her lifetime.

On our way back, we had lunch at the Taktshang Cafeteria located at the mid-way point. The menu was fixed, but the spread was ample with red rice, noodles, dal, a variety of vegetable dishes including Ema Datshi, and egg-curry. After a delicious and hearty lunch, we headed back down the rest of the way, with the sun going down, and the light fading fast in the pine forests. The corresponding dip in temperature made us unpack our backpacks to layer ourselves with woollens.

It was about four o’clock when we reached the base point. Namgay was waiting, blood-red spittle streaking down the side of his mouth. I bought a few souvenirs, mostly fridge magnets, while my partner purchased some stone jewellery. The souvenirs were cheaper than both Paro and Thimphu. If one is planning to take home souvenirs, it is here, at the end of the day, that you will get the best bargain. Namgay proposed that we visit a dzong a little further away, but we were exhausted and instead opted for the cold bed of our hotel.

In the evening, we walked about the main street. In the distance, across the river, Rinpung Dzong was lit up. It looked like a magical castle suspended in the air. At a café, called the Mountain Café, we spent a long time reminiscing about our trip with a slice of back-forest and a cup of cordyceps tea. The tea was smooth; it didn’t actually have a taste, but definitely made us warmer. Cordyceps is a type of parasitic fungi that attacks a host, generally an insect larva, and eventually replaces the host tissue and sprouts out of the host, almost resembling a caterpillar. It grows in the wild at very high altitudes and is handpicked by locals, who consider them sacred. It has been used as a traditional Chinese medicine for centuries. Outside it had begun to drizzle, and the shops had started to close. We exited the café and headed to our hotel, wrapping ourselves in whatever warm we had.

DAY 7: PARO – A DAY TO RELAX

The sky was overcast, and we spent the morning in our hotel. Later, we explored the town on foot and had lunch at a small eatery; red-rice, dal and chicken. The town of Paro is small, with just two principal streets bisecting it, parallel to each other and the river. The main street has souvenir shops and cafés, while the other is lined with hotels. There is a vegetable market, a taxi stand, and a park gym. We walked around aimlessly and found half-a-dozen boys playing football near the river. The schools were closed for winter, and the kids spent their days helping their parents. In one shop, we found a girl, about ten years old, responsible for managing the counter. She was sharp and witty and negotiated well to my partner’s bargaining skills. She inquired if we were Indians, and after we purchased a sweater and paid with our currency, she carefully inspected it with amazement in her eyes. From another departmental store, we bought a couple of bottles of peach wine, and from another small bakery, got ourselves a couple of croissants.

DAY 8: PARO – KOLKATA

We woke up at 3 am. The lights were out, and the electric heater had long stopped working. It was still drizzling outside, and our teeth chattered in the cold. In the flashlight of our phones, we packed and went down to our taxi that had arrived on time. No one was up at the hotel. Sangay, the receptionist, had instructed us the previous evening to leave the main door ajar on our way out. It seemed strange to leave the door like that, but I guess it summarises the nature of the people of this fascinating country.

The town was pitch-dark, and the taxi’s headlight revealed the snow that had collected by the roadside through the night. It had been snowing all night, and we didn’t have the faintest clue. My heart grew heavy; if only we could have stayed another day and witnessed snowfall. A car had run into a ditch, and the taxi driver laughed saying that they might have skidded off the road and crashed. My partner and I exchanged glances, wondering if we should stop and check, but the driver dismissed our concerns with a wave of his hand.

We reached the airport. Our flight was on time. We completed our exit formalities and waited in the departure hall, scanning through the over-priced souvenirs on display. We had a light breakfast; a sandwich and a cup of coffee. Then as the day-light dawned, and we headed to board our flight, I beheld the most breathtaking scene I have ever witnessed in my life. The misty mountains surrounding us were covered in fresh snow. The sun that was hidden behind the clouds, now peeked for a generous moment to reveal the splendour around us, like a magician unravelling his final act in front of an awe-struck audience.

If you have enjoyed reading the above post, please consider buying a copy of my book. KNOW MORE